Urban Heritage Conference October 2014: the Challenges of Advocating for Marvellous Melbourne’s CBD Modernism

Given the heritage study work that the City of Melbourne has undertaken in the last three years preparing heritage controls for hundreds more buildings, this is a great time for this conference.

However, despite being a significant period in Melbourne’s cultural and architectural history, post-war modernism is scarcely represented in the CBD on either the City of Melbourne’s heritage overlay or the Victorian Heritage Register.

Currently only one post-second world war building in the CBD has an individual municipal heritage control. This is despite the recent excellent efforts of the City of Melbourne strategic planners backed by most of the City’s Councillors. Just four post-war places, an equally miserable number, are included on the Victorian Heritage Register, which recognises places of state significance.

In the context of this conference on urban heritage, the questions I discuss are:

- what has happened about protecting post-war modernist places in Melbourne’s CBD?

- what is the role of NTAV?

- what is the justification for protecting post-war places?

- what has this stuff got to do with protecting ‘’Marvellous Melbourne’’?

- why is this stuff so challenging to Ministers?

- isn’t this the sort of stuff NTAV was fighting against in the 60s and 70s?

And crucially, will the designation of the heritage of modernism conform with or disrupt the conventional attributions of, and decision-making around, significance, particularly about fabric? Is the emergence of heritage significance of modernism some natural and evolutionary and ultimately predictable expansion of what is considered heritage (by certain advocates), or is it an opportunity to reassess and challenge the glibness of old appeals to notions of authenticity, truth and honesty in heritage which so often go unchallenged? That is a very broad question, the answer for which can perhaps emerge from recent, current and future analysis of what it is about modernism that we don’t want to lose.

The National Trust for Historic Preservation in US has been busy for several decades advocating for preservation of post-war places. And the Daily Mirror in the UK recently reported how the National Trust in the UK has taken up the modernist preservation cause with gusto. The Trust in the UK is right now championing Balfron Tower, Poplar (Erno Goldfinger, 1967) – grade II listed, and once dubbed Britain’s ugliest building. They have restored Goldfinger’s own flat and conducted ‘’pop-up’’ open day tours –

National Trust adopts ‘Britain’s ugliest building’ as star attraction for two-week architecture tour

In disbelief at this move, The Mirror reported “James Bond author Ian Fleming was so disgusted by Goldfinger’s designs for terraced houses in Hampstead that he used the architect’s surname for the villain of his seventh novel.” An heroic building became an instant villain, but its reputation is now being revived, and the tours are sold out.

Advocates for statutory protection of modernism in Melbourne such as the National Trust and DOCOMOMO have faced their own vocal critics, both from some Trust members and some of the community who say we are not doing enough to value this stuff, as well as predictably some developer groups, media, other types of Trust members, other sections of the community and not least planning ministers saying what on earth are City of Melbourne and the Trust up to in pursuing this stuff?

For example, one commentator, The Urbanist said: It is fallacious to assume the community regards buildings of one era e.g. the 1960s as being as valuable as the building of another era…It isn’t inevitable that the wider population will in due course supposedly come to value the total carpark with as much affection as they feel for the Windsor (1880s hotel). And The Age reported our current Minister for Planning saying he did not want to see the city “awash with structures built in the 1950s”. Well, there is no chance of that, as this stuff is disappearing pretty quickly, and we are losing something significant.

In Victoria the Trust classified ICI House in 1985 and a specialist 20th century classification committee studied and classified buildings for a number of years in the early 2000s. In 2006 we hosted a seminar with architects about emerging heritages post-1950s. Our Iphone App Lost, Melbourne’s Lost 100 launched in 2012 includes a number of significant lost modernist buildings.

Architectural commentator Elizabeth Farrelly wrote in the Sydney Morning Herald in 2006 of Melbourne’s tradition of “daring to care about culture” compared well to Sydney’s cultural timidity. Our advocacy is about critical assessment of the significant legacy from all periods and we now like to use the term “Marvellous Melbourne’s Modernism.”

When it is asked at this conference where are the young people I can tell you that they are lapping up this modernist legacy. There is an appetite for this stuff and it is with younger audiences! Our friends at Architours Shelley Freedman, Esther Sakito and co. run very popular walking tours patronised by Gen Y, and we have happily collaborated with them and produced a walking tour booklet as part of our 2014 heritage festival.

However, back in the world of statutory planning, in recent years the progress towards the protection of post-war architecture by local and state planning authorities in Melbourne’s CBD (and in Victoria) has remained slow, glacially slow. From a select group of modernist places within the CBD proper and just north of the CBD put forward in the last three years by City of Melbourne all remain in limbo courtesy of the Minister for Planning.

But at least we have gotten the issue being played out in the media. The Age newspaper in March 2014 wrote a long piece on the issue of this new and challenging heritage. It reported: “The National Trust has created a list of 13 especially ”challenging” relics from the post-war period it believes are ripe for protection, including some of the city’s first concrete high-rise offices.” (The story ranked only behind the Oscars and a story on the UK royals: “Royals snub Melbourne!” Prince Charles probably told them not to bother coming!)

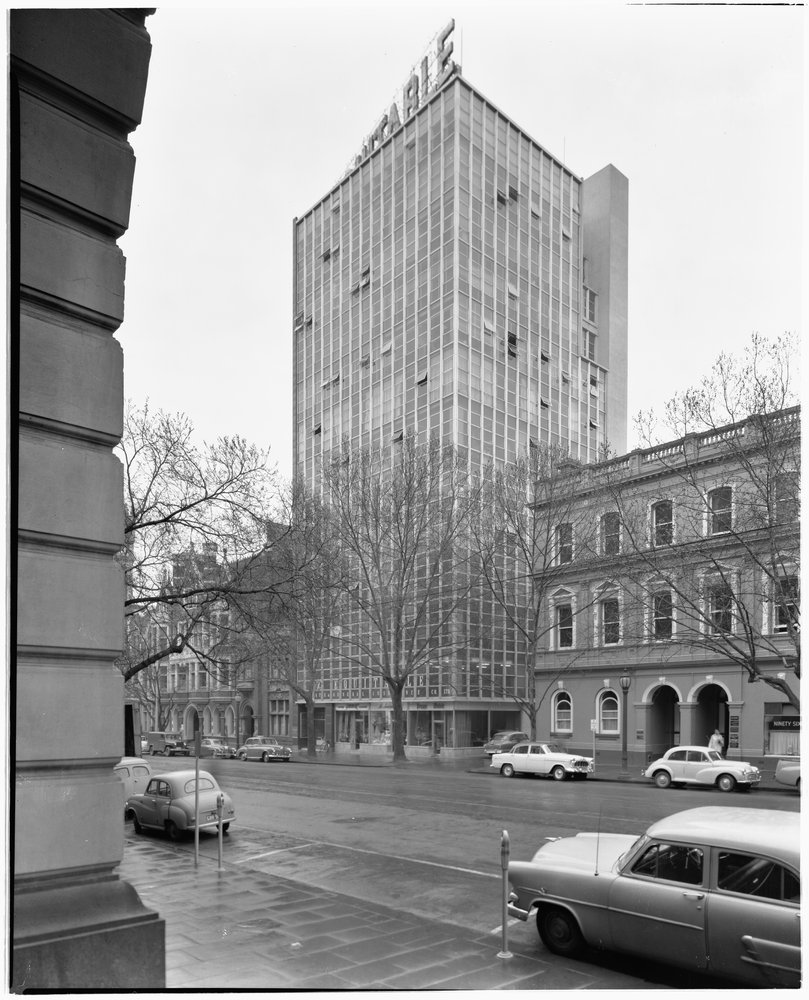

Gilbert Court, 100 Collins Street (above), the first post-war all‐glass total curtain wall building, built in 1955, and located in the Collins Street East heritage precinct and is one of a handful of modernist buildings with protection on the City’s CBD list. Note how it was built to the then height limit of 132ft, 40m. However, whilst A graded, it is included more by chance than design! The statement of significance for the precinct states:

Gilbert Court, 100 Collins Street (above), the first post-war all‐glass total curtain wall building, built in 1955, and located in the Collins Street East heritage precinct and is one of a handful of modernist buildings with protection on the City’s CBD list. Note how it was built to the then height limit of 132ft, 40m. However, whilst A graded, it is included more by chance than design! The statement of significance for the precinct states:

At all times until the post 1939-45 war period, redevelopment took place in a quiet and restrained manner with an emphasis on dignity, harmony and compatibility with the intimate scale and pedestrian qualities of the street. Key attributes of the precinct: the buildings remaining from before the Second World War. The statement of significance and permit policy provide scant protection for one of Melbourne’s most significant buildings!

Over the last 30 years, the City of Melbourne has documented the city’s heritage assets in more than 30 area studies. Starting in the mid-1970s several of these relate directly to the CBD. The first controls were enabled in 1982, and there are now 11 precincts in the CBD covering hundreds of places, and around 300 individual controls in the CBD.

However…there are no post‐war buildings currently with an individual overlay in the CBD except for four on the State Register (ICI House, BHP House, Eagle House, and, very recently the former Hoyts Cinema Complex).

In (Marvellous) Melbourne, the heritage of post-war buildings is especially ‘challenging’ to an idealised past and heritage present. Modernist buildings were largely designed to stand in contrast to the low-scale, decorative Victorian and Edwardian buildings they replaced. The 1930s promoted “street architecture” supported by the RAIA Victoria Medal promoting architectural sensitivity to the street context. Modernism’s emergence as a heritage issue has challenged those who believe that preservation efforts in Melbourne should be directed purely towards an idealised Victorian city. (No doubt the Trust is partly to blame for this state of affairs).

The 1956 Olympics was a key moment in the modernising of the city and Melbourne was in the international spotlight at the far end of a contracting empire – what were its aspirations to be part of a braver, bigger, newer, post-war modern world? The independent planning panel C186, considering nine post-war buildings for listing, reflected on some of the expert evidence presented to it on the post-war period. The evidence claimed the period was

more significant for its role in destroying Melbourne’s nineteenth century character rather than being important in its own right. The Panel believes, however, that while it can be viewed as a period of destruction, it should also be viewed as a period of creativity.

The rear-view mirror to the 1970s, reviving the vision of an idealised Victorian city, preserved up to the Second World War, which whilst undoubtedly suffering substantial post-war losses and creating mourning and sentimentality for all things Victorian (but with a preference for anything Georgian-looking), contrasted of course to those post-war austerity notions of Victorian vulgarity, wanton excess, boom and bust, and an architecture to match.

And whilst the losses in the 1960s and 1970s were awful (and organisations like the Trust had far more campaign losses than wins), the assessment of post-war places as heritage has brought into stark relief the inevitable tension between an essentially (although intermittent) Victorian character of Melbourne (because most buildings are not from that period) and the year-zero pretensions of modernism (for Melbourne’s purposes let’s call it 1956).

The fusion of post-war planning and modernist architecture was an international phenomenon that was starting to help shape Melbourne’s new architectural language and planning. It was a language of order, rational planning, utopianism, optimism, and revolutionary schemes on a grand scale. Graeme Butler in his 2011 heritage study for the City said:

In 1957 Victoria’s State Building Regulations Committee decided in favour of modifying height limit laws for city buildings. The 132 foot (40 m) height limit introduced in 1916 had been exceeded by ICI House in the previous year, and it was now replaced by a system allowing greater heights in individual cases, dependent upon floorspace and light angles… The increase in height of buildings in the central city soon suggested other implications for the form of the city. The fad for open space at ground level was to sweep away the propriety of the 1930’s street architecture and usher in a new era of plazas and landscaped public space.

The unfortunate legacy of the 1840s Hoddle grid was of course virtually zero public open space and Melbourne’s planners have struggled with that legacy ever since.

The 1964 Planning Scheme for the Central Business Area formalised plot-ratios, encouraging plazas and setbacks. Gaps in the street wall appeared. Proprietorial street architecture, built to the street line, rising up to the height limit, was to be radically and excitingly challenged. Public open space was created inside the boundary line, public art was brought down to street level, there was a blurring, in a controlled fashion, of public and private domains.

In 2011 the City of Melbourne proposed to expand local heritage protection to an additional 99 buildings in Melbourne’s central business district, known as Amendment C186. The City has attempted to update its overall list about once every decade since the 1980s. In 2013, the Minister for Planning, the ultimate decision-maker on these matters, confirmed permanent heritage controls for C186 for 87 places out of a proposed list of 99 buildings spanning the period 1850s-1930s. That was safe territory. But, the bulk of those excluded comprised all of the nine post-war buildings.

The exclusion was despite the independent Planning Panel’s support for the application of heritage overlays for the post-war places. The Minister for Planning refused to include the buildings, citing a need for further study. That further study, hinted to as being prepared by Heritage Victoria, has not been forthcoming. The subject buildings sit in limbo, unprotected. Most recently, another Planning Scheme Amendment (C198) included the former TAA Building at 50 Franklin Street completed in 1965. This is another crucial amendment, and could reclaim some of the ground lost due to the Minister’s earlier refusal of nine post-war places. The decision of the Minister for Planning is (anxiously) awaited.

Objections to listing modernist places

Some critics have argued that the measure of significance should be critical contemporary acclaim – be it in architectural media, or by awards – but we cannot rely on architecture awards as a guide! Whilst the Royal Insurance Building, and others won awards, the possible lack of critical acclaim was addressed (and conceded by an objector) in evidence to the C198 Panel – This imbalance in critical study is not in itself an impediment to considering heritage significance. Victoria’s architecture awards were suspended between 1943 and 1952, and from 1953 till 1964, and (yet) a great deal was accomplished in those periods.) Remember, Southland Shopping Centre beat the National Gallery of Victoria in 1968. The relative reputation of those buildings has changed dramatically in the intervening years.

Fetish for fabric

We have heard the word authenticity mentioned a few times at this conference. The challenge of modernism is its lack of concern for fabric. The spirit and ethos was for modern technologies and experimentation. Newness is an essential component. Material is less important than the values they represent.

Obsolescence

Issues put up against registration include obsolescence of function, inefficient use of space, energy efficiency deficiencies. In response however the City of Melbourne’s 1,200 buildings program for upgrading CBD offices has included several successes with sustainability and efficiency upgrades of post-war places earmarked for heritage controls.

Permit policies

If protected, what protection do they have at permit stage? There is the problem of existing City of Melbourne heritage policies being directed towards Victorian, Edwardian and interwar places. It is now reviewing its heritage policies and is considering principles for adaptation, re-use and creative interpretation in the review.

The most controversial commentary has been over aesthetics

Raising responses to the perceived ‘ugliness’ of some post-war buildings. Planning Minister Matthew Guy raised eyebrows in January this year with his view that ‘people use the term Brutalist architecture to legitimise ugly buildings, but I don’t think we should be saving ugly buildings in Melbourne’.

Comparative analysis

The C186 Panel criticised the comparative methodology put up by opponents in the matter of post-war buildings: “we find that they are not helpful as while they are all similarly tall buildings, they are not directly comparable in other respects: they adopt mixed approaches to cladding; all of the comparators have different approaches to the manner in which they meet the ground and provide an entrance to the building; the comparators are also mixed in the manner in which they sit on their sites and include buildings which variously are in plazas or on podiums or are built to the street.”

Need for further study….

The exclusion of the post-war group was, as already explained, a decision of the Minister for Planning and is thought to have been made in part on the basis that there was a need for further study of buildings of this period. Reported by The Age, Mr Guy said “The buildings, some of which are Brutalist architecture, will be subject to further review. Some of them are questionable in their architectural significance to the city,” he said.

Either the Minister’s further work (or rather that of his department), if ever seriously contemplated, wa snever undertaken, or if it was, it (and the Minister’s response) has never materialised.

Our work with our volunteer Built Environment Advisory Committee over the last year has culminated in a comparative study document, a copy of which is available online. In this document we have examined the nuanced architectural development of the period and arranged it by types. Modernism was a new aesthetic, but not a singular aesthetic. We trust this document will be of value in future amendments.

Examples:

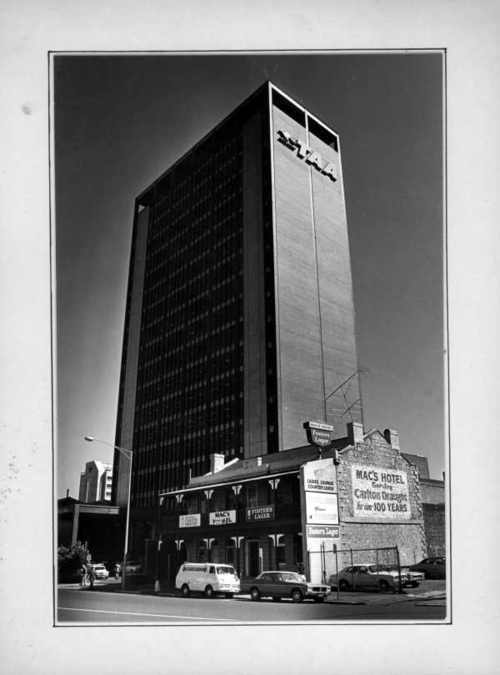

Royal Insurance Building (1965) 430-442 Collins Street

The Royal Insurance Group Building, designed by Yuncken Freeman Architects, and completed in 1965 is one of the most elegant of Melbourne’s post-war skyscrapers.

The pre-cast concrete cladding panels are finished in sombre black polished granite. The small setback from the street and the position on the corner of a lane allow the building to appear free-standing, aloof from but not dominating the surrounding Collins Street commercial development.

Winner of the Victorian Architecture Medal, the building was the most accomplished of the early pre-cast concrete clad office blocks, leading the field away from the light-weight curtain wall facades in Melbourne of the previous seven years. It was a prelude to a number of the city’s best skyscrapers by Yuncken Freeman.

It was nominated by the Trust for the VHR in 2007 and rejected by the Heritage Council in 2008.

The Heritage Council registration committee concluded that the substantial nature of the alterations at ground and the previous mezzanine levels reduced the significance of the building to the extent that it did not satisfy the Criteria used to assess cultural heritage significance. It was also later rejected by the minister as part of the C186 amendment.

Total House

Total House (Bogle & Banfield, 1965) at 170 Russell Street, nominated by MHA. Following a hearing before the Registrations Committee of the Heritage Council in February 2014, the Heritage Council determined to add Total House to the Victorian Heritage Register. The Heritage Council was satisfied that Total House is a notable, highly intact, distinctive and early example of Brutalist architecture in Victoria with a particularly Japanese influence.

In his expert evidence on behalf of the National Trust, architectural historian Simon Reeves submitted that from the late-1950s, Japanese influence could be seen in many aspects of Australian culture including architectural design and concluded that Total House demonstrates the key characteristics of the Brutalist class of buildings and is ‘a significant benchmark in the early development of the style in Victoria’.

However, this building has become a cause celebre for us and Melbourne’s other post-war heritage advocates because the building is proposed for demolition and redevelopment.

Two months ago the owner lodged a Supreme Court writ claiming that the Heritage Council had erred in its application of the Heritage Act in its decision-making.

The Heritage Act principle being challenged is the well-established two-stage process of separating out assessment of economic impacts from listing decisions and permit decisions. Economic considerations are exclusively reserved for the permit process.

So both the application of the Heritage Act and the place of post-war modernism are at stake in the forthcoming Supreme Court appeal. It is unclear what appetite/support the Minister for Planning will give his department in this legal battle, given his very public comments and his perceived view of Total House and other modernist architectures being “”ugly”. The hearing is scheduled for next April 2015, and NTAV is actively considering how it can support the Heritage Council defend both this building and the Heritage Act. Total House is set to be a totem for the preservation of post-war modernism in Victoria.

Hoyts Cinema Complex

A happier story is that of the former Hoyts Cinema Complex in Bourke Street. It was nominated by the National Trust in 2013 for the Victorian Heritage Register. Designed by Sydney architect Peter Muller in 1969, it is one of Melbourne’s most outstanding, distinctive (and difficult to categorise) post-war buildings. It displays Muller’s interest in structural engineering as a means to inspire architectural form. The use of Chinese-inspired bracketing for the wide eaves overhang resulted in a very unusual upside-down pagoda-like form. A hearing before the Heritage Council on the matter was scheduled but later stood down as extraneous issues relating to mechanics of the listing were resolved between Heritage Victoria and the Owners Corporation. (It is strata titled)

TAA

The TAA –which we have dubbed ‘’the bronzed Australian’’ – has jumped all the hurdles for local listing with City of Melbourne, and now awaits the decision of the Minister for Planning. Completed in 1965, the building was conceived and expressed as a tall vertical slab, set well back from the street, with a low-rise wing to the rear. The rear wing no longer exists. A sophisticated modern design with slick external finishes, the exterior of the building represents a notable use of architectural bronze across an entire building façade. .(Simon Reeves gave expert evidence on behalf of the Trust).

Former National Mutual, Collins Street, 1965

This significant building is now being demolished. There is a short NTAV video on youtube with an interview with Philip Goad. It was by Godfrey & Spowers Hughes Mewton & Lobb, with Leith & Bartlett in association. The former Western Market site, owned by the City, having been considered for near 100% site coverage in the late 1950s, was reconsidered in the role of half investment office tower and half public plaza, set over 1 acre, larger than any city green space before it. The tower and the plaza together are one of the best examples of the modernist planning ethos of towers setback behind a plaza introduced in the late 1950s in Melbourne.

Prof. Miles Lewis wrote in Melbourne: The City’s History & Development that “…the implications for the city were potentially dramatic. The modernist vision of a city of high rise towers set amidst landscaped greenery at ground level seemed imminent, provided that major corporations were able to purchase large city sites or consolidate a number of titles.”

Three suggested Precincts

- An ensemble on the Corner of Bourke and Queen Streets, literally and metaphorically a modernist crossroads. Three buildings by Bates Smart & McCutcheon, and one by Leslie Perrot. Sadly one is already being demolished, the

- Queen Street, south, west side – the modernist wall of glass comprising the Canton Insurance Building, 43-51 Queen St, by Bates, Smart & McCutcheon, (1957) and Norwich Union Insurance, 53-57 Queen St, by Yuncken, Freeman Brothers Griffiths & Simpson (1957).

- William Street – Eagle House, BHP, and Estates House all by Yuncken Freeman, with the Bates Smart & McCutcheon& Skidmore Owen Merrell AMP tower across the road.

Conclusion

The heritage of post-war modernism is about new heritage, new challenges, new opportunities, and certainly an opportunity for the National Trust to actively pursue these challenges. The response to tours of these places by youth is the excitement of being shown new layers and shapes in the city, and of buildings previously ignored revealed as an important layer in development of the city.

Modernism is a fantastic subject for advocacy, supposedly universal truths that were soon corrupted, but the optimism of the post-war period and its impact on our urban environments, its inventiveness and distinctiveness and experimentation and claims for better futures is what we do not want to lose.

Melbourne’s competitive edge, its appeal to youth, can be and is being played out through these places, whether some like it or not. So this is about new heritages, big statements, bold movements, it is a worldwide movement, and Melbourne needs to be part of it.

+ There are no comments

Add yours