Footscray Psychiatric Centre: concrete, lithium, and a future for our brutalist buildings

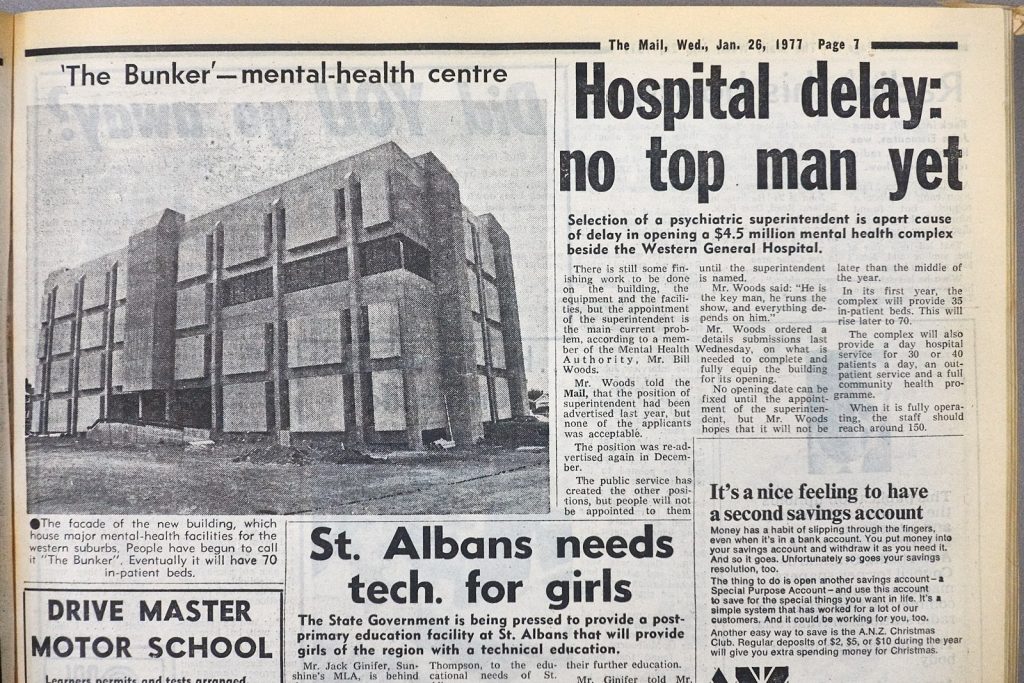

Featured image: Footscray Psychiatric Hospital, image courtesy of John Jovic.

In July, National Trust Advocacy Manager Felicity Watson presented at a public information session on Brutalist architecture hosted by Maribyrnong City Council. The event was organised following the recommendation by Heritage Victoria to include the Brutalist Footscray Psychiatric Centre in the Victorian Heritage Register (VHR), which was nominated by the National Trust, and aimed to highlight the significance of Brutalism both locally and globally.

Brutalist architecture is a significant marker in the history of our built environment and the function of our communities within it. Additionally, these buildings present creative opportunities for adaptive re-use to accommodate the needs of our communities today. A summary of the presentation is detailed below.

Psychiatric Treatment in Victoria

In nineteenth-century Victoria, the treatment of mental illness was characterised by large asylums and hospitals, many of which are represented on the Victorian Heritage Register, including Willsmere in Kew (now a residential development), Beechworth Asylum (Mayday Hills Hospital), and Caloola (former Sunbury Mental Hospital) at Jacksons Hill. While many of these complexes operated well into the twentieth century, and have later additions that demonstrate changes in approaches to the treatment of mental illness, their layout, architecture, and landscape settings demonstrate nineteenth-century attitudes to mental health care.

Willsmere (Kew Lunatic Asylum) 1856, SLV H39357/33

From the 1950s, changes in the understanding of mental illness and public policy shifts emerged in Victoria. This period saw the increasing influence of psychiatry, with major reforms in mental health services introduced by the Mental Hygiene Authority, led by Dr Eric Cunningham Dax. The mid-century period also saw significant developments in treatment. In 1949, Australian doctor John Cade pioneered the use of lithium to treat bipolar disorder, which was in common use internationally by the 1970s.

A new phase of mental health treatment, which became known as deinstitutionalisation, saw the rapid reduction of patient numbers in large psychiatric hospitals, many of which had been established in the nineteenth century. A series of community mental health centres were planned and built across Victoria between the 1960s and 1980s, and the establishment of an early treatment centre at Footscray was a priority for the Mental Health Authority. In 1973, the Commonwealth Mental Health and Related Service Assistance Program provided funding for eight new community mental health services in Victoria, including Footscray.

Footscray Psychiatric Centre

Footscray Psychiatric Centre was designed as an early treatment centre by the Victorian Public Works Department in the early-1970s, with construction beginning in 1974 and completed in 1976. The facility opened in 1977, with the opening of an outpatient clinic and community mental health service.

The building is a four storey structure, with all external faces executed in board-marked off-form concrete. The exterior is a bold textured pattern of projecting elements over the basic rectangular form, creating a striking massive, apparently windowless, monolithic building. Projecting deep rectangular precast elements representing a pair of patient rooms on each floor, alternating with projecting vertical structural piers, create the main pattern on all four facades, with ducts and stairs contained in larger scale vertical elements that project further out, and above the roof, terminating in chamfered tops. The interior has a core of lifts and service rooms, with bedrooms, treatment rooms, day rooms, and offices around the perimeter. The National Trust has assessed it as being one of the most visually striking and unique of all Victoria’s large-scale Brutalist style buildings.

Beds were closed in the facility from 1993 and the building ceased to function as a psychiatric centre in 1996. It is currently used for storage by Western Health.

Footscray Psychiatric Centre is an important marker of mental health treatment in Victoria, because it reflects major changes in the understanding and treatment of mental illness in the twentieth century. This is reflected in its size, which is much smaller than existing nineteeth-century institutions, and also in its internal layout of accommodation, treatment rooms, and activity spaces.

There are challenges in the conservation of places associated with trauma, and we recognise that people in the community may have strong and complex attachments to this place. However it is also important that the heritage places we project reflect the complexity of our history, so we can recognise and reckon with the past.

Concrete futures

In recent years, recognition of the historical and architectural significance of Brutalist buildings has increased, both among architecture enthusiasts and the public at large. Publications such as the Concrete Melbourne Map, which includes the Footscray Psychiatric Centre, demonstrate an appreciation of the dramatic aesthetic qualities of the style.

Concrete Melbourne Map, Blue Crow Media, 2019.

As with all historic buildings, there is a need to find viable new uses for our significant Brutalist buildings which respect their architectural and historical significance. Two examples in Sydney demonstrate how we could re-imagine Footscray Psychiatric Centre for the future.

In 2013, the NSW Department of Education acquired the UTS Ku-Ring-Gai campus in the northern suburbs of Sydney with the vision of creating a large education centre, repurposing the heritage-listed 1970s Brutalist building.

Lindfield Learning Village (former Ku-Ring-Gai UTS campus), Lacoste + Stevenson

The design, led by Lacoste + Stevenson Architects, uses playful and colourful geometric additions which contrast with the existing Brutalist architecture. The fit-out is totally reversible, in line with good heritage practice, and is also recyclable. It is sympathetic and complementary, while contributing positively to the experience of students and staff.

Since 2015, a community campaign led by the Save Our Sirius Foundation has been underway to save the Sirius building in The Rocks, designed by housing commission architect Tao Gofers and finished in 1979. The complex was built to rehouse public tenants who were displaced during a redevelopment of The Rocks in the 1960s and 1970s. In 2015, the NSW Government made a decision to sell the building, which was not heritage protected. The NSW Heritage Council recommended listing for the building in 2016, but this was denied by the state government. Nevertheless, the strength of the community campaign to save the building resulted in an announcement in June 2019 that the building would be “refurbished” as an apartment complex rather than demolished, having been sold to an investment firm for $150m.

Lessons can also be learned from the repurposing of industrial buildings. Once out of favour, industrial heritage contributes to a sense of place, and recognition of history. The repurposing of buildings and materials can provide creative opportunities, and provide a canvas for new layers and uses.

What next for Footscray Psychiatric Centre?

You can have your say on Heritage Victoria’s recommendation to include Footscray Psychiatric Centre in the Victorian Heritage Register by writing to the Heritage Council of Victoria by Monday 16 September 2019. Anyone can request a review of the decision by the Heritage Council, which may conduct a hearing. The Heritage Council will then make the final decision whether to permanently include the place in the Victorian Heritage Register. Visit the Heritage Council’s website for further information.

The inclusion of the Footscray Psychiatric Centre in the VHR would not prevent change or control the use of the building. Instead, it would ensure the architectural and historic values of the place are considered if there is a proposal to change, redevelop or demolish the building. Additionally, it would provides an opportunity for the community to comment on future plans.

+ There are no comments

Add yours