HERitage: how women shape the cultural landscape

In December, the National Trust presented a panel discussion in partnership with Parlour exploring women’s heritage in Melbourne, as part of the MPavilion’s MTalks series, held at the 2018 pavilion designed by architect Carme Pinós. To interrogate this topic, we invited a panel of experts from across the heritage and history sectors to engage in a discussion chaired by Felicity Watson, National Trust Advocacy Manager:

- Professor Harriet Edquist, Director, RMIT Design Archives at RMIT University and Professor of Architectural History

- Dr Celestina Sagazio, Historian and Manager of Cultural Heritage of the Southern Metropolitan Cemeteries Trust.

- Renee Muratore, registered Architect and Heritage Consultant at Trethowan Architecture

- Dr Cristina Garduño Freeman, early career academic and Research Fellow of the Australian Centre for Architectural History, Urban and Cultural Heritage (ACAHUCH) at the University of Melbourne

From left: Felicity Watson, Dr Celestina Sagazio, Renee Muratore, Prof Harriet Edquist, Dr Cristina Garduño Freeman. Photograph by Marie Luise, courtesy of MPavilion.

Click here to listen to a recording of the event via MPavilion’s MTalks podcast. Reproduced below is the introduction, presented by Felicity Watson.

I begin by paying my respects to the Traditional Owners of the land on which we are meeting, the people of the Kulin Nation. We pay respect to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander people and recognise they were the first people of Australia.

Over many years, there has been much research about the history of women in our city. I acknowledge work of our speakers Celestina Sagazio and Harriet Edquist in this field, as well as Julie Willis, Justine Clark, Jane Jose, Bronwyn Hanna, Renate Howe, Naomi Stead, Dimity Reed, Anne Vale, and many more. But there is still more work to be done to recognise the presence of women in the built environment and our cultural landscapes.

This discussion will look specifically at the role of women, generally in Melbourne, but there are also other stories that urgently need to be examined – those of Aboriginal people, of migrants, and of queer and non-binary people, groups which are often marginalised or ignored in mainstream conceptions of heritage.

This research has only scratched the surface of this rich subject area. But sometimes what’s evident on the surface is telling. Because it’s at the surface where most of us dwell, and glean the information that helps us understand the world around us.

A simple search on the State Library of Victoria catalogue revealed just 26 records associated with Marion Mahony Griffin, an architect who left a significant mark on our state and our country.This is in contrast with the 623 records for Walter Burley Griffin, her husband and collaborator.

Marion is practically a footnote in her own entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography. And this is one of the most prominent female architects ever to have practised in Australia.

Capitol Theatre, Melbourne, designed by Marion Mahony Griffin and Walter Burley Griffin. Photograph by Wolfgang Sievers, 1977. (State Library of Victoria)

The work of historian Clare Wright in her retelling of the story of Eureka, has shown that it is vital to re-examine accepted truths, and revisit and re-read records with curiosity. And buildings and landscapes are documents, too, that invite re-examination with fresh eyes.

In looking at the presence and absence of women in the cultural landscape, some strong themes emerge. One of the most obvious examples of the absence of women is in historic statues and memorials. Beyond the odd statue of Queen Victoria or a mythological figure, few women, and indeed non-white people, are commemorated or memorialised in this way. In 2017, the Age reported research undertaken by Worimi woman Genevieve Grieves, which found that of 520 memorials, statues and monuments, only a dozen were not “dead, white, men”.

Our statues of male figures include explorers, colonisers, soldiers, poets, footballers and music personalities. But if you’re a woman and you want to be memorialised in bronze or stone, you have to literally be the Queen or a saint.

The presence of women is more evident in public art which is more recent. Aboriginal artist and Wurundjeri woman Mandy Nicholson collaborated with artist Nadim Karam, to create Gayip, who represents the ceremonial meeting place of the clans of the Kulin Nation. Nicholson also designed the ceremonial shields along Birrarung Marr, which forms part of the complex and evocative Birrarung Wilam installation by Vicki Couzens, Lee Darroch and Treahna Hamm.

Birrarung Wilam installation by Vicki Couzens, Lee Darroch and Treahna Hamm. Photograph by Jessica Hood.

The playful work of Deborah Halpern, including Angel, can also be seen along the Birrarung.

The waves of Inge King’s Forward Surge are a feature of the St Kilda Road Arts Precinct, and now included on the Victorian Heritage Register. King designed the work to encourage physical interaction.

Inge King’s Forward Surge. Photograph by Rennie Ellis, 1992, reproduced with the kind permission of the Rennie Ellis Photographic Archive.

The Great Petition in Burston Reserve, designed by Susan Hewitt and Penelope Lee, was unveiled in 2008 to commemorate the centenary of women’s suffrage in Victoria. I don’t know whether it was designed to encourage interaction, but it is a popular place for skateboarders.

Other stories about women are embodied in the fabric of buildings, but not evident without accompanying documentation or interpretation. This social history is often not well protected through our systems of heritage protections, which privilege aesthetic and architectural values over social and historical values.

This has led to the destruction of significant places associated with women’s history. A prominent example of this from recent years is the Princess Mary Club on Lonsdale Street, a 1920s hostel which provided accommodation for women moving to Melbourne from the country for work and university. A permit to demolish the building was granted in 2015 to make way for a 33-storey tower, which is currently under construction. The building’s owners, the Uniting Church, argued that the condition of the building was so poor that it was not economically viable to restore it. It had sat derelict for decades.

Just down the road, the former Queen Victoria Hospital, was established at St David’s Welsh Church in 1896, one of only three hospitals in the world founded, managed and staffed by women. In 1946, it moved to the former Melbourne Hospital Buildings, where it became the biggest women’s hospital in the British Empire. The hospital closed in 1987 when its services were relocated, and many women campaigned to protect the buildings from demolition. Only the main entry block was saved, which is now home to the Queen Victoria Women’s Centre.

Then there are buildings created by female architects and designers, which are still relatively rare, particularly in a historical context. One of the most well-known examples is the Lyceum Club, a club for professional women, designed in 1957 by Ellison Harvie of Stephenson & Turner. Significantly, the building’s interiors, as well as alterations and additions, have also been designed by women, including most recently an addition by architect Kerstin Thompson. Incredibly, this building does not yet have permanent heritage protection, although it has been classified by the National Trust as being of state significance.

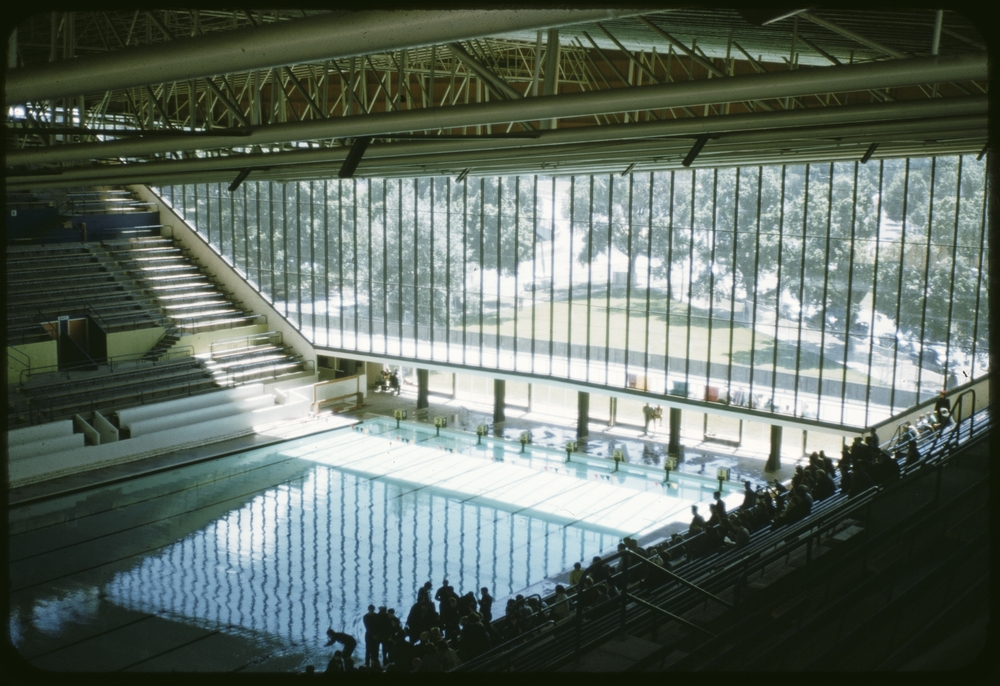

Another prominent female modernist architect is Phyllis Murphy, who practiced with her husband John Murphy on many new builds and restoration projects, one of the most well known being the Olympic swimming pool, designed with Kevin Borland and Peter McIntyre.

New Olympic Swimming Pool, Olympic Park. Melbourne, designed by Kevin Borland, John & Phyllis Murphy & Peter McIntyre. Photograph by Peter Wille. (State Library of Victoria)

In Beaumaris, the work of Sylvia Tutt has recently come to light, with her house at 89 Oak Street under threat, along with many other modernist gems in the suburb. Tutt designed four homes in Beaumaris, and despite not being formally trained in architecture, graced the cover of the June 1966 Australian House and Garden. Her work is a reminder of the significant role that women have played in domestic architecture, and particularly in interior design and decoration.

Historically, women have been more prominent in landscape and garden design, such as Edna Walling, who started her landscape design practice in the 1920s, and modernist Grace Fraser. While many people are familiar with the work of Edna Walling, Grace Fraser is less well known. Through her work with landscape architect John Stevens she worked on landscape projects for Monash University, ICI House, the National Mutual Building plaza, Royal Children’s Hospital and Western Suburbs Memorial Park. Her most well-known work in private practice is the design of the Australian native garden at Royal Park. She was also influential in conservation advocacy in the Mornington Peninsula.

Women have also shaped Melbourne’s cultural landscape through civic leadership and activism. While Jane Jacobs is one of the twentieth-century’s most influential urbanists, many Australian women have also shaped our cities, and local government has proven to be particularly fertile ground for female leadership. In her role as the first female Lord Mayor of Melbourne, architect Lecki Ord was instrumental in introducing policies to protect heritage places, work continued by her successor Winsome McCaughey. Both were highly engaged with the community through grassroots activism, and contributed to making Melbourne more livable and attractive to residents.

These examples just scratch the surface of the presence and absence of women in Melbourne’s cultural landscape, but they raise some interesting questions and issues.

The National Trust is grateful to our generous speakers, and to the MPavilion team for hosting this event.

+ There are no comments

Add yours